グループE DiaryDay4 (9/6)

TEPCO Decommissioning Archive

This morning we visited the TEPCO decommissioning archive. This was a museum in relation to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011 and the subsequent decontaminating and decommissioning process.

We found the museum to be very informative, as it was able to give background and context to what the company was thinking. We found it interesting how the museum experience started with an apology, framing the issue as a sensitive one. Yuichiro was explaining how there sometimes is sentiment amongst the Japanese population that there is a responsibility of TEPCO to own up to the mistakes and explain how and where the situation went wrong.

We reflected that the nuclear power plant design was based on the last 50 years of tsunami history and predictions. This clearly shows that the plant was not adequately prepared for the possible severity of geohazards seen in the region, or to foster collaborative efforts between science and industry. Even in yesterday’s outcrop we observed that there have been large tsunamis impacting japan for hundreds of thousands of years. Not adequately considering the geohazards in the region just reiterates why we need to continue research to understand the topic of geohazards, not just in Japan but worldwide. Due to Japan’s geological location on an active subduction zone, it is essential to always be considering the risk of major natural disasters.

We weren’t sure if the museum presented the science information in a way that was accessible to the general population. We thought that some of the nuclear explanations would be confusing without a background in science. However, we think that they did a good job of distilling the important information of how the reactor malfunctioned, and the order of events leading to the nuclear disaster. Yuichiro mentioned that even for people who can read Japanese, the poster explanations are quite high level, and might not be informative for the general public.

We reflected that the layout of the museum was obviously designed for Japanese speakers as opposed to tourists, which made understanding some of the information more difficult for us who couldn’t read Japanese. This was interesting as the messages of apology and mistakes were then more targeted at the domestic population that was largely impacted by this disaster. However, there is still the right for the international community to understand the disaster and how it occurred. It was interesting to see how the museum had considered the target audience for the presentations and demonstrations. This is also important in regard to international science communication, as this disaster should be a lesson in safety for all nuclear power plants, and infrastructure when considering the influence of geohazards in design. It is important to consider with all infrastructure that we are creating a built environment within a natural environment, proving that we need to be working in conjunction with natural hazards, and understanding the local geohazards to ensure that we can adequately prepare for disasters in the future.

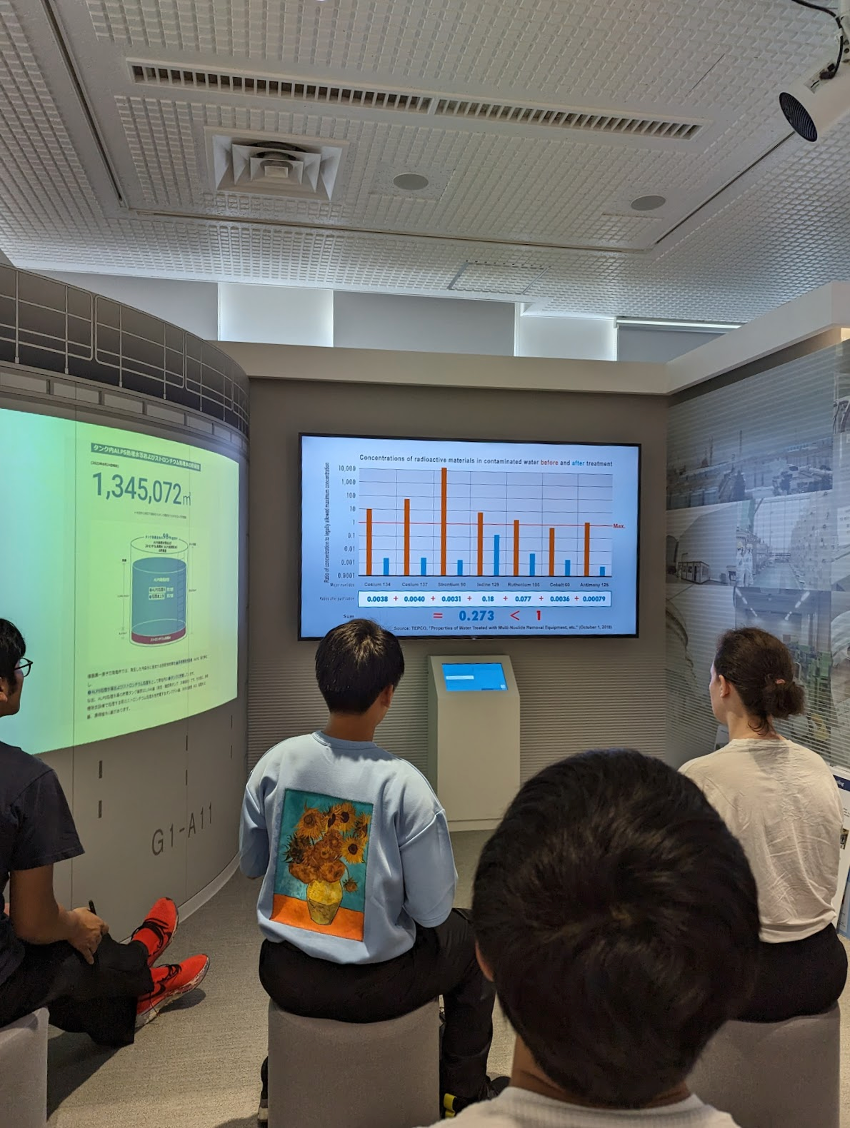

We reflected that we found the explanation on the treated nuclear water to be interesting and explained the process in a relatively informative manner. However, when it came to the remaining concentration of tritium, we thought that this could be better communicated by connecting to personal emotions. By reiterating safety, this could help communicate to members of the public how they will or won’t be affected by the release of treated water. We considered how there was no explanation on the impacts of radiation on humans at the museum. This relates to one of the first lectures given by Will Grant, who talked about the importance of empathy and connection in science communication, especially in moments of fear or concern.

Bonus Observations from the Bus Trip

We reflected on the importance of science communication, and specifically in teamwork with scientists. Lauren explained from her perspective that the ways in which scientists communicate with each other is very different to how science communicators communicate with the public. This is a difference that is important for all communicators and scientists alike to reflect on and work together.We reflected on the importance of science communication, and specifically in teamwork with scientists. Lauren explained from her perspective that the ways in which scientists communicate with each other is very different to how science communicators communicate with the public. This is a difference that is important for all communicators and scientists alike to reflect on and work together.

On the bus, Yuichiro told us about the Fukushima province paper article on the fish they had tested in the treated water. They had researched the concentrations but didn’t find any tritium in the fish. The testing they conducted reminded us of some of the research conducted in the aquarium at U-Tokyo. We then talked about the ideas of public vs private science, and how the influence of bias and funding can often have a substantial impact on results. Yuichiro was telling us that it is common in Japan to have collaboration between professors and private companies in research. This is similar to Australia where research can be biassed by funding sources, or there can be a lack of transparency in where these sources come from, such as mining companies funding research on endangered species.

During the trip, we reflected that we have been driving along the same roads that people used to evacuate during the tsunamis. In some areas, the lack of visible scars is concerning, but seeing the radiation metres every few kilometres acted as a constant reminder of the history and trauma of the place. The destruction and abandoned houses that have been reclaimed by nature were also evident during the drive, particularly yesterday close to the reactor in the Fukushima province. Terraces and open plains also remind us of how far the tsunami would have been able to travel on land, in this flat geographic setting.

In regard to the radiation metres, Moss saw one that read 1.9, and then shortly after saw another one that was 0.2 and another around 0.3. Ren and Kai explained that this anomalously high one was in a road cutting, meaning the radiation was coming in from 3 sides. This stresses that some areas of Fukushima are still experiencing high levels of radiation, and that communication and research should remain at the forefront of everyone’s minds.

Another roadside observation made us consider the different flora and fauna in Japan and Australia. We saw signs warning of warthogs, racoons, and monkeys on the road, whereas in Australia, there are kangaroos, koalas, and wombats. The geologists tried out their hands in science communication explaining how plate tectonics has led to evolution of different species over millions of years that all have a common animal ancestor. In relation to the frequency of natural disasters in Japan we were curious if the plants or animals in Japan are more adapted to an environment prone to natural disasters? How does this manifest in their morphology? Do some of the plants have deeper root systems to account for the high density of earthquakes? How have the natural disasters of the region shaped evolution?

Mio Kamitani’s Workshop on Disaster Recovery

The workshop later in the day was really interesting as it explained more of the first hand and personal experience of natural disasters. It changed the learning experience from more theoretical and based in pure science to something that was connected in real world scenarios and their implications.

Mio made a clear link to the impact of geohazards on industries such as fisheries. This was in her implication that the tsunami and the future reconstruction efforts limited the ability for the fishing industry to return to pre tsunami levels. This was also reflected in the communities decisions, like the building of a taller seawall which was supported by most groups other than the fishing community.

We talked a lot about the different kinds of disaster communication and reconstruction communication following disasters. We compared the strategies of leaving all decision making to the government or contract workers, vs including the wider community. Obviously this is heavily influenced by the kind of disaster, but it was still interesting to consider. We talked about the fact that the government experiences a level of disconnect from the situation when it comes to decision making. This can mean that it might not accurately reflect the wants and needs of the impacted community. This ties into the idea that it is very difficult to conceptualise what you don’t know. For example the 14.5m sea wall. While this might be heavily backed up by science, we will never be able to fully understand what life would be like surrounded by a 14.5m sea wall.

However, when involving the community in decision making, it is important to consider how and when this occurs. Mio brought to our attention how the timing of surveys can impact decisions. Asking the community to vote on a situation only several months after the disaster does not consider the emotionally charged elements of the situation. The community might then have different opinions to what they feel in the future. We also considered community behaviours during the disaster, for example how it was common for the people of Osutchi to go up the mountains when an earthquake happened to avoid the tsunami risk. We connected this to our discussions of human behaviour from Will’s case study regarding L’Aquila and how citizens would gather in the Piazza.

We also found the idea of the compound effect of hazards to be interesting. The Otsuchi region experienced extreme fires following the tsunami disaster which had an exponentially more disastrous impact on the region. However, these fires are not necessarily a natural hazard as they were fueled by man-made factors. We made the connection between this situation in Otsuchi and what we learnt about earlier today and yesterday regarding the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. Natural or geological hazards can have a flow on effect for other man-made disasters. All the future implications of a geohazard event need to be considered when regarding both the mitigation and communication strategies used. When considering the fires we also thought it was very interesting that usually ocean water was used to put out forest fire, but due to the debris washed into the ocean from the tsunami, this was not possible. We considered how this related to the work on microplastics, and that there is a short term disaster issue of the fire, but a longer term disaster issue of microplastics which are now beginning to impact on human health through bioaccumulation in fish, and other aspects associated with ocean plastic.

There was an important discussion on hair wash times. Yuichiro told us about how pretty much everyone in Japan will wash their hair every day – somewhat due to people sweating a lot in the heat of summer. However this is much more varied in Australia. Us girls washed our hair every 2-3 days, while Moss really rocked the boat and washed his hair once a month. We were all shocked.